The Visitation of Archbishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii) to Vormsi, 1900

In Christian communities, inspections by bishops (known as visitations) have long been used to instil discipline amidst the clergy and ensure that orders are being carried out in parish churches. This was the case, too, in the imperial Russian Orthodox Church. However, the large size of dioceses and the short tenures of Orthodox bishops (frequently moved at the whim of the state) meant that nineteenth-century visitations were sporadic at best. Consequently, bishops were regularly regarded by the clergy and laity alike as distant administrators rather than as fathers to their dioceses. This also meant that, in practice, authority in the Orthodox Church often devolved to more local agents, such as deans (priests in charge of a group of several parishes).

Bishop Platon (Kulbusch) visiting Suure-Jaani in 1918 (EAA.5410.1.60.53)

The following translated source is an extract from the diaries of Father Jakob Vaarask (1862-1936) wherein he describes a visitation by Bishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii) (1854-1928) to the island parish of Vormsi in July 1900. Vormsi was a rather unique congregation in that rather than serving a Russian, Estonian, or Latvian population, it catered to a group of several hundred Swedish speakers who had converted from Lutheranism to Orthodoxy in 1886 [1]. These parishioners were representatives of a small minority group (later known as the Estonian Swedes) that had been present in Estonian lands from at the very least the thirteenth century: they were to remain until they fled to Sweden during the Second World War. However, the Orthodox parish had already been in long decline by the time the Estonian Swedes left: with the end of the Russian Empire, the restrictive religious laws that prevented people from converting away from Orthodoxy vanished, and most of the faithful defected either to Lutheranism or to one of the Evangelical Christian groups active on the island.

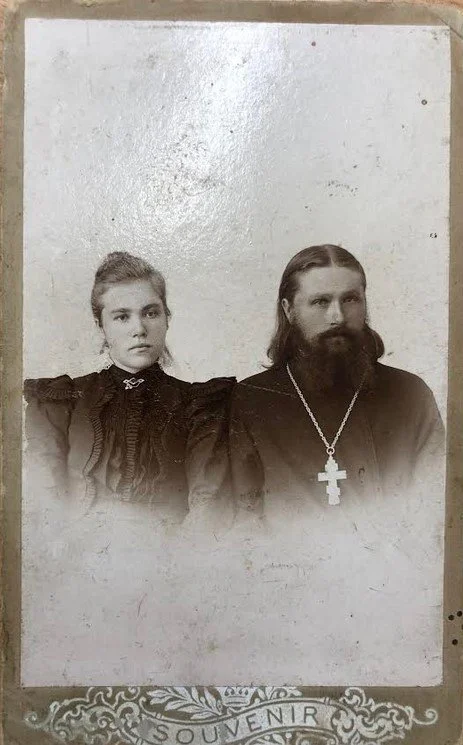

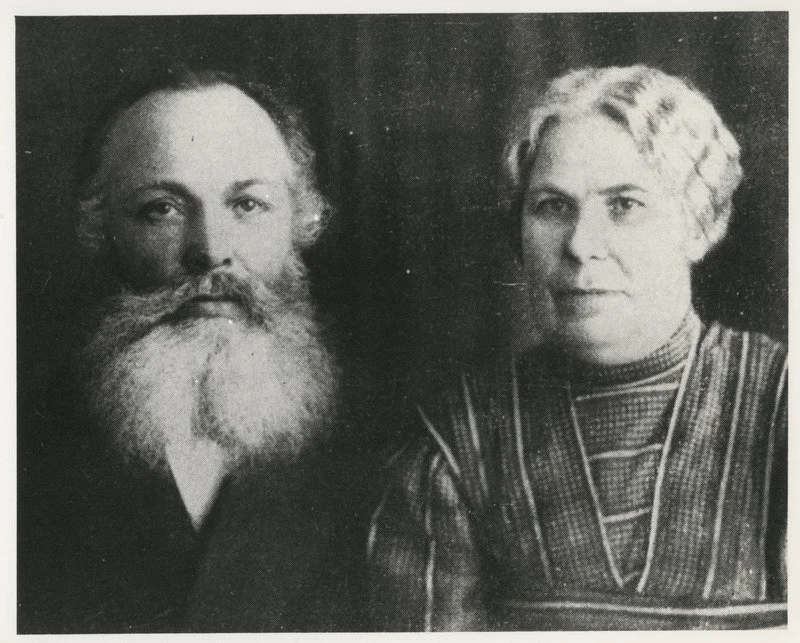

Father Jakob Vaarask and his wife Helena

Father Jakob Vaarask began his career on Vormsi as an Orthodox teacher in 1887: after several years in this position, he became the community’s priest in 1894, a job he held until 1926. As the extract reveals, Vaarask was quite the personality: acerbic, combative, and proud to the point of arrogance, his time as an Orthodox clergyman was regularly punctuated by conflicts with those above and beneath him. Although diligent and industrious, Vaarask regarded his role as a priest as only one part of his life plan to become a landowning pedagogue and philosopher: consequently, he began to gradually neglect his parish until finally being defrocked for abstenteeism in 1926. Bankrupted by bad credit in the early 1930s, Vaarask died of kidney disease in 1936: sitting in the Estonian Historical Archive, the 44 volumes of his diary (covering from 1885 to 1917) have mostly been ignored up until today.

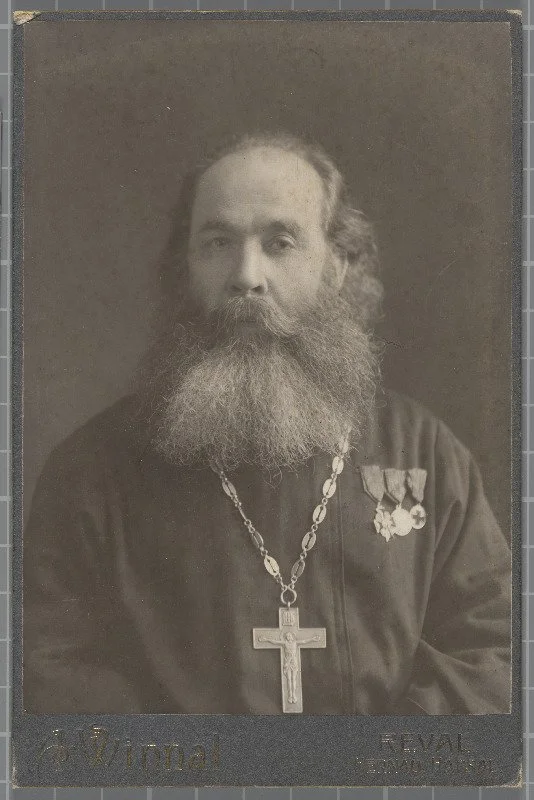

At the time of the visitation in 1900, Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii) had already been bishop of Riga diocese for three years: this occasion marks the first and only time that he and Vaarask met during Agafangel’s tenure, which lasted until 1907. The prelate has subsequently attained a reputation as a liberal amidst the predominantly conservative Russian Orthodox episcopate. Some of this reputation derives from his time in Riga diocese: following the chaos of the 1905 Revolution, he called on the government to show clemency to revolutionaries and organised a local church congress to implement progressive reforms in the Church [2]. Agafangel is best known today for the leading role he played in the Russian Orthodox Church during its persecution in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. He died of a heart attack in 1928.

Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii)

The following extract has the rare dint of being simultaneously informative, entertaining, and absorbing. Vaarask’s idiosyncrasies both as a narrator and a personality are on full display, including his efforts to defend his vegetarianism and teetotalism to a befuddled collection of mainland Orthodox clergy. The enormous effort that visitations required from the clergy are revealed, as are some of the everyday aspects of priestly life, especially the venomous collegial rivalry often at play. Agafangel is humanised, shown less as a distant diocesan overlord and more as a sympathetic and courteous man out of his depth in this rather strange parish. The diaries also highlight how both Vaarask and the parish he helmed sat on the frontline of a religious struggle between Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, and Evangelical Christian groups, with police power clearly being used, if rather clumsily, to support the Orthodox side.

extracts from the Diaries of Father Jakob Vaarask

Sunday 23 July 1900

I got up at 8 a.m. and went to church at 9 a.m., where we held the liturgy. During the communion service, Spuhl [3] gave a sermon in Estonian [4], and I gave a sermon in Swedish on the ‘Feeding of the 5,000.’ Helena, Juula, and Lobjakas sang [5]. There were few people in church because it was raining heavily. Before the veneration of the cross, I announced for the second time that the bishop would be visiting on the twenty-fifth of this month. Today, there were no Sunday school children or teachers in church or around.

When I returned home, I ate. After the meal, I assigned the sacristans to clean the church utensils and sent Moll to Sviby with Släd and Rönnkwist [6] to Fällarna with my maid, carrying orders to deliver messages in the villages on both ends of the island, instructing children to come for the bishop’s reception on Tuesday and if they do not come, they will not be given any parties in the future. Later, Moll came by personally, and I discussed the matter with him; he then went to the eastern villages to deliver the orders.

Afterwards, the [Lutheran] sacristan Lindström came to collect payment for painting the cupboard, and I spoke with him for some time. When he left, I went to the church, where […] items were cleaned and prepared, I gave a new curtain for the royal gate [7] to be arranged, and we held Vespers. When I returned home, I ate, strolled outside, and went to bed at midnight.

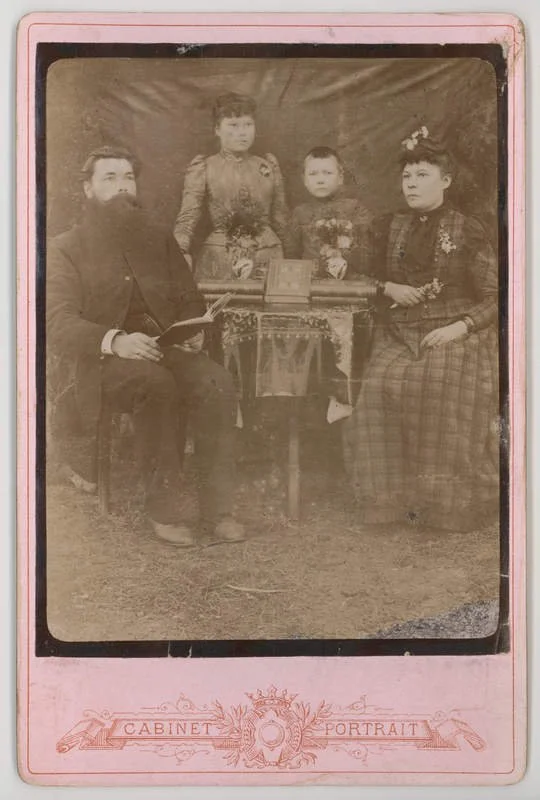

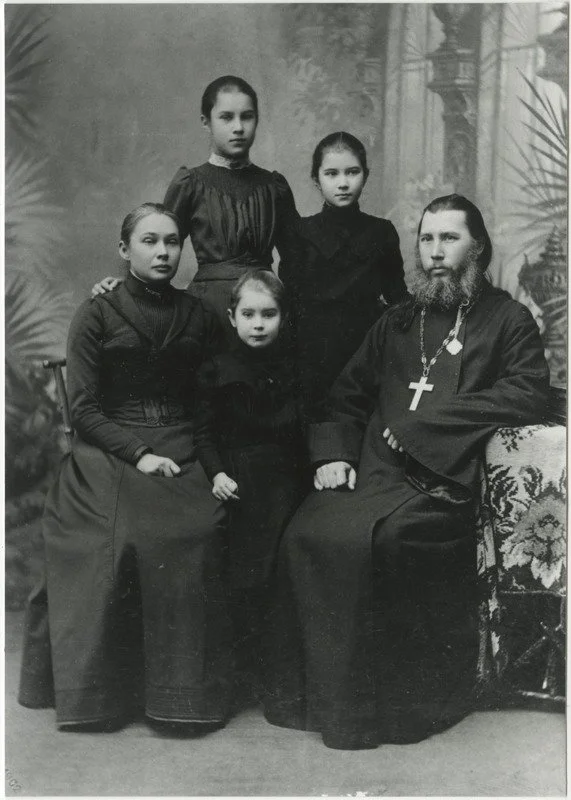

Jaan Spuhl (Orthodox sacristan and schoolmaster on Vormsi), his wife Juula, and two of their children (HMK_F6409)

Monday 24 July 1900

I ate milk and bread in bed, got up at 8 a.m., and went to the church, where the sacristans were washing the altar floor. I had the school cupboard, which had been used for the church archive until now, moved to the northern classroom.

Later, Kreek’s son [8] was sent to Söderby with Tomas’ horse to fetch the bishop’s cook and food supplies, as the postman had specially delivered word of their arrival. Afterward, I spoke with the constable about matters [relating to] the ceremonial archway, etc.

Six horse-drawn carriages arrived from Söderby, bringing a load of birch leaves for making a ceremonial archway at the churchyard gate. The leaves were arranged in a row on either side of the path leading up to the church steps. The women who brought the birches also washed the church floors, as no one else was available because rye harvesting began everywhere today.

After that, I personally cleaned the church’s Gospels and other items that the sacristans were unable to clean. The new curtain for the royal gate was set up, new coverings were placed on the altar and offertory table, and we organised everything in the church, including the linens and archive cabinet. Afterward, I went home to organise the chronicle and the liturgical journal [9], completing the writing of entries. I also arranged the library and set up the new study, which will serve as the bishop’s room, as well as organising all the other rooms.

In the evening, the bishop’s cook arrived along with a woman from Haapsalu [10] bringing food supplies. Intense food preparations then began. All this was overwhelming, as no household helpers were available, and there were too many tasks to manage. Everything had to be done personally: organising the church, schoolrooms, home quarters, garden, and yard, even overseeing rooms that were the police’s responsibility. While putting everything in perfect order today, I discovered missing items that had to be acquired immediately, and anything dirty or out of place had to be rectified. The sheer variety of tasks and their management was enough to drive one mad.

In the evening, floor coverings were obtained and laid out from the church steps to the altar table, and I explained to the sacristans what needed to be done for the bishop’s reception tomorrow.

Then I returned home, ate, conducted a singing rehearsal in the classroom, and explained the bishop’s reception arrangements to the sacristans’ families. I went home, reviewed everything, and finally went to bed at midnight.

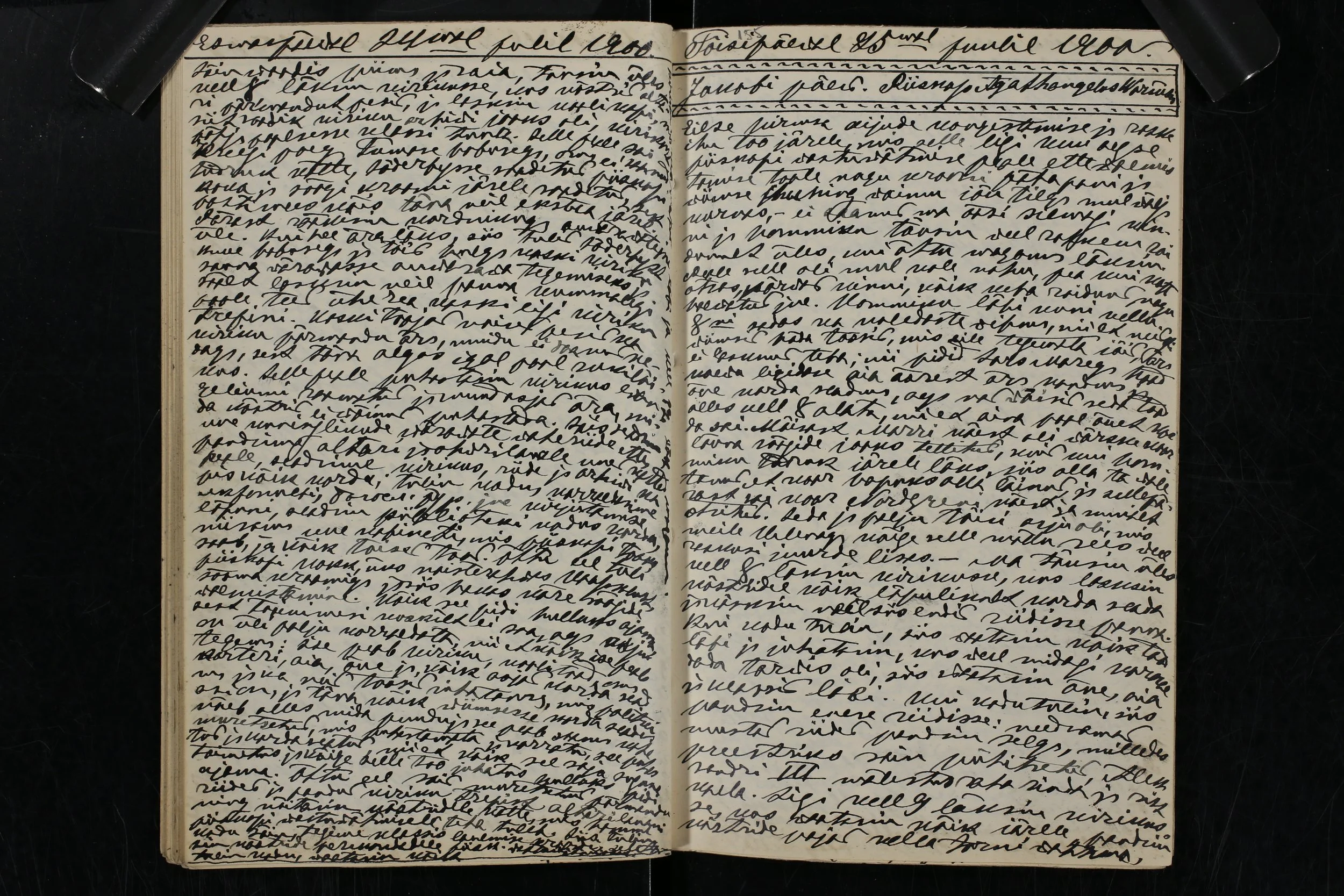

Jakob Vaarask’s diary entries for 24 and 25 July 1900

Tuesday 25 July 1900. St James’ Day. Bishop Agafangel on Vormsi.

The exhausting physical and mental preparations over the past month for the bishop’s reception drained every last bit of my strength. I couldn’t sleep at all last night, and when I woke in the morning I felt more exhausted than when I went to bed. On top of that, I had a terrible cold, my head felt like it was in a vice, my ears were blocked, and my whole body felt fatigued, as if paralysed.

The morning brought pouring rain until 8 a.m., preventing the final tasks from being completed. For instance, Lars and Mari were supposed to clear away the area near the well and tidy up the yard, but they could only start at 8 a.m., meaning only half the yard could be cleaned. From the manor, fresh cream had been ordered from Mari for the midday meal, but when the girl went to fetch it, Mari lied, claiming the cream had spoiled, so we had to scramble to find cream from Nordgren [11] and others. These and other complications only added to the chaos for Helena and me.

I got up at 8 a.m. and went to the church, where I instructed the sacristans to finalise everything and then get dressed. When I returned home, I inspected every room, giving instructions for anything that still needed tidying. I then checked the yard, the garden, and the classrooms.

Back home, I dressed myself in the same black vestments I wore when I was ordained as a priest, pinned my Alexander III commemorative medal [12] to my chest, and hung my cross around my neck. Around 9 a.m., I went back to the church to inspect everything and posted the sacristans’ sons in the bell tower as lookouts. The plan was to receive signals: one from the manor pasture when the bishop was seen at Kubassen’s, and another from Hullo hill when he reached the Hullo meadows. Upon the first signal, the bells were to ring once; on the second, all the bells would ring. However, the police had not sent anyone to open the gates near the sauna, and the birch-leaf-lined paths along the roads were still unfinished. By 9 a.m., not a single person had arrived to greet the bishop. Had it not been for the timely arrival of Slät, who opened the gates just in time, the situation would have turned into a scandal since the bishop would have arrived at locked gates, as only the pedestrian gates near the sauna were open.

Hullo meadow, 1935 (EFA.554.0.183033)

In the church, I ate some hard sugar to gather strength, but it upset my stomach and caused a fever, putting me in a critical condition for this important reception. I was sure I would fail today. My health has always tormented me during life’s most significant moments, but I have managed to overcome this until now thanks to my iron character. This time, however, my spirit was so drained that even my character seemed powerless.

Due to the intense fever causing heavy sweating, I removed my vestments and sat in the sacristy at the back of the church, assuming there was still time. I trusted the boys in the tower to see the signal and begin ringing the bell at the right moment, giving me enough time to dress. Unfortunately, the boys were careless and missed the signal entirely. Spuhl ran into the sacristy, informing me that the dean [13] was already here and the bishop was close behind. Only then did Kreek’s son begin ringing the bell.

I dressed in my ceremonial robes and exchanged a few words with the dean, who expressed satisfaction with the state of the church and its arrangements. He was particularly impressed with the new, beautiful, and expensive items I had procured for the church. While inspecting the spare sacred vessels, he remarked, ‘Oh, how beautiful! Mine are so faded and poor.’

Carrying the cross on the paten covered by the aër [14], I walked from the back of the church toward the entrance just as the bishop’s carriage entered through the gate near the sauna. Near the door, I paused in front of a small carpet. On either side of the carpet stood large candleholders with burning candles. On the northern side was churchwarden Appelblom with the vessel of consecrated water.

The bishop alighted briskly from the carriage, entered the church, and stopped in front of me on the small steps, where his episcopal mantle was placed on him and his staff handed over. The bishop cast a lively glance at me, which I met with a strong and confident gaze. He then turned his gaze toward the back of the church while his vestments were adjusted. From the very first look, I liked the bishop immensely. His face radiated energy, kindness, and wisdom.

Once vested, I handed the cross to the bishop for veneration. He blessed himself with consecrated water, and I turned immediately, leading the procession toward the back of the church with the cross on the plate. The dean and Leisman [15] followed, one on the north side and the other on the south. I aimed for a slow ceremonial pace, but the nervous dean, fearing that the bishop might walk faster than us, grabbed my arm and hurried me along, ruining the grandeur of the procession.

At the ambon [16], I stepped aside to the north edge, allowing the bishop to walk directly to the back of the church along the carpet. Then I stepped back onto the carpet, waiting as the choir finished singing the Swedish hymn On Duty.

During this time, the dean had a critical look. I had given him the service booklet before the bishop’s arrival, but he had misplaced it. Now, needing to begin the prayer service, he hurried back to the rear of the church, found the booklet, and returned just in time, and I began the prayer service with enthusiasm, speaking clearly and with resonance, as my voice was in good condition. The service was conducted in Swedish. Finally, the Dismissal [17] was recited by the bishop himself in [Old Church] Slavonic [18]. He did it so softly that it sounded like a faint whisper after my readings.

Father Aleksandr Bezhanitskii (the dean of Haapsalu), 1911 (EFA.661.10.110631)

Afterwards, I proclaimed Many Years [19] in Swedish, but confusion ensued. The dean and Leisman disrupted the order of the song. Since the Swedish words for Många år are shorter, our choir sang the phrase nine times to the melody. After proclaiming Many Years for the emperor and the imperial family, the choir followed the established pattern. However, when it was time to proclaim for the bishop, Leisman allowed only three repetitions. The dean then abruptly took the paten from my hands and placed it before the bishop, who immediately placed the cross on it. This action prevented me from wishing Many Years for the Vormsi parish and all Orthodox Christians. Thus, the dean, Leisman, and the bishop made an error that I could not correct. Otherwise, I would have had to insist that the bishop take the cross back so I could make the proclamation, which would have been a humiliating scandal for him.

The dean, Leisman, and the bishop himself did not realise the mistake they had collectively made, since none of them understood a single word of Swedish. Similarly, none of the attendees noticed the error. After the singing of Many Years, the bishop proceeded to the altar at the back of the church, and I followed him there immediately. At the altar, the bishop asked detailed and lengthy questions about the parish, the sacristans, the schools, and so forth. I gave him clear, thorough, and lengthy explanations about everything, particularly regarding the sectarian beliefs and activities [20] on Vormsi. The bishop requested a written account of this so that it might be possible to prohibit the Baptist faith in the area [21]. I explained that I had already submitted a detailed report on the matter to Archbishop Arsenii [22] in 1895. However, the bishop insisted on receiving a new one.

Regarding the language in schools, the bishop seemed liberal-minded [23]. When I explained that children cannot properly learn Russian without first understanding their mother tongue, he fully agreed. He also did not criticise the sacristans’ lack of proficiency in Russian after I explained that they first needed to master Swedish.

During this long conversation, with the dean standing behind me and the choir singing continuously, I got to know the bishop’s mindset fairly well. I realised that he was a progressive thinker in matters of faith and sought to investigate everything rationally. This conversation lasted about an hour. The bishop then inspected the items on the altar and asked if there were more to examine.

I replied, ‘Of course, of course, there are more.’

The bishop asked, ‘Why didn’t you bring them here so I could see them?’

Me: ‘There wasn’t enough space here.’

The bishop gestured, pushing the items into a pile, and said, ‘Look, there is plenty of space here!’

Me: ‘I cannot just pile things up carelessly; everything must be in proper order. If you wish to see them, you can inspect them in the cupboard where they are kept properly.’

The bishop did not press further after my decisive response. Then I told him that it would be beneficial to address the people as previous bishops had done, [as] the people always wish to hear something from their spiritual leader. The bishop hesitated and replied, ‘The people did not come to church voluntarily; the police forced them in.’

Me: ‘That is not true; they came voluntarily.’

The bishop: ‘I saw the police driving people into the church myself.’

Me: ‘That is a misunderstanding. The people were hesitant to enter before you arrived, and after you came, the police simply directed them, showing that it was now time to enter the church. Nothing more.’

The bishop could no longer argue further, and I recognised his weak spot: he was unable to speak to the people without prior preparation. Sensing this, I pressed more firmly for him to give a speech.

The bishop: ‘They will not understand me if I speak in Russian.’

Me: ‘I will immediately translate it into Swedish and Estonian.’

Now the bishop’s last arguments were refuted, and he was visibly flustered. Finally, he said, ‘Could you perhaps say something to them on my behalf?’

I: ‘Of course, of course I could, but the people expect to hear something from you.’

The bishop, visibly discomforted, pleaded, ‘Could you not address them in my name?’

I didn’t want to torment the bishop any further and agreed to do as he asked. I ascended the ambon, where the bishop also followed me. Standing to the north of the bishop, I delivered a rather lengthy and deeply inspiring sermon in Swedish. Through this, the bishop, Leisman, the dean, and others could see that I possessed the gift of oratory in abundance [24]. I can speak extemporaneously for as long as needed, with eloquence and enthusiasm, something no bishop in Russia could do like me. In delivering speeches, I am as free as a fish in water. Without the slightest preparation, I can passionately and eloquently speak for hours, as thoughts and sentences flow into my mind like a river during the act of speaking. The more I articulate, the more ideas seem to gather in reserve. I never lack material on any subject. My poetic mind enables me to become all-seeing and all-knowing once I am fully inspired.

After the sermon ended, the bishop began blessing the people and testing the schoolchildren. A few small Sunday school children had come, and I instructed them to recite prayers in Swedish and make the cross before the bishop. Stenholm’s son from Sviby read in Russian quite well, considering it was his first winter learning the language.

After examining the children, the bishop called the sacristans forward. He asked where they had completed their training, where they had previously worked, and so on. I was anxious about Spuhl, but he responded briefly and satisfactorily to the questions. Kreek, who was more proficient in Russian than Spuhl, made more mistakes.

Next, I brought Helena, Kremnikov’s daughter, and others forward to meet the bishop. The bishop said to Helena, ‘You also sing?’ Helena replied, ‘Yes, every Sunday.’ The bishop responded, ‘That is good.’

Finally, I presented the churchwarden [25] to the bishop. Through my translation, the bishop asked whether he would be willing to continue as warden when his current term ended, etc.

The bishop distributed small crucifixes to the people, as well as saints’ lives to the schoolchildren. There was a decent crowd in the church, as the rain had interrupted the rye harvest that morning. However, many people could not attend due to the harvest season; in every village on Vormsi, the rye had already ripened excessively because of the rain, and delaying the harvest further was impossible.

The Russians once again displayed their well-intentioned crudeness in the church. The district chief, his deputy, and others urged people toward the bishop’s blessing rather roughly, alarming the Swedish women. At one point, the district chief even dragged a woman with an infant to the bishop by force, despite her feeble resistance.

I asked the woman who she was, and she answered that she was Lutheran. I relayed this to the district chief, who let her go, saying, ‘I only wanted her to bring her child for a blessing.’

After blessing the people, the bishop began to inspect the church and remarked that our church was more beautiful [26] than others he had seen on Saaremaa, Muhu, and Hiiumaa [27]. The beauty of our church was significantly enhanced by the new, elegant church utensils and their tasteful arrangement, though our church is not unattractive even otherwise.

Ruins of the Vormsi Orthodox church today

The bishop then examined the northern cupboard, looking over the church vestments. He questioned why such a fine phelonion [28] was being used for rites [29]. However, when I explained that I would not compromise on quality during sacred services, especially not in villages where many people gather, including non-Orthodox, and it’s also the most easily foldable phelonion for packing, he approved my reasoning.

Next, the bishop inspected the new southern cupboard, which had been freshly painted just last week, costing 30 roubles and is [text missing] feet wide, [text missing] feet deep and [text missing] feet high, and houses the church archive. The bishop praised the order and creation of the cupboard and instructed the dean to use it as a model for other parishes. He expressed surprise at the poor condition of the older items, because when I took over from Orlov [30], the church was truly impoverished, and I have since procured almost all new items.

Finally, the bishop inspected the candle cupboard and inquired about the church’s finances. With this, the church inspection concluded. The bishop exited the church with the dean and Leisman, while I went to the altar, closed the royal gates, placed the altar coverings back, removed my vestments, and joined them outside on the church steps.

From there, I walked with the bishop, answering his questions. First, he asked about the size and condition of the church land. I explained that the land was essentially barren and described our efforts to establish gardens. I pointed out Spuhl’s garden [31], and the bishop, initially heading toward the path near the church, agreed to enter through the gate when I suggested it.

Once inside, the bishop blessed the garden and wished success for the horticultural endeavours. I explained the purpose of the tree nursery and its goals. From Spuhl’s garden, we went to the southern classroom, where the bishop praised the cleanliness and order. We then visited the school kitchen and finally the northern classroom, where I showed the bishop the six school desks that I personally funded. I also explained the issue of desk shortages [32].

Vormsi Orthodox church and school building, 1934 (EFA.554.0.183018)

Here, I made the dean and Leisman’s earlier false claims abundantly clear. Pointing to a school desk purchased with state funds, I said: ‘Look here, this desk is meant to seat no more than three children according to school regulations, and we have only nine such desks. That is enough for 27 children. However, the dean reported to the Riga school council [33] that we had desks for 40 children.’

At this, the dean, standing behind me, angrily whispered to Leisman, trying to justify himself. But the undeniable truth left him speechless. I turned to Leisman, pointing again to the crown’s desk, and said: ‘You oversaw the creation of these desks, and they cost, what, five roubles each.’

Leisman gave no response. Then I pointed to Rönnkwist’s desks and said, ‘I also set the price for those desks at 5 roubles, and for that, I received a reprimand from the school council, accusing me of acting against my conscience by demanding the price of new desks for old desks. Now, look for yourselves, are these desks overpriced at 5 roubles each!?’

I then angrily explained how I spend hundreds of roubles from my own salary every year for the benefit of the people while using only a fraction for myself, etc., etc., yet I am accused of self-interest! This clearly made an impression on the bishop, and he began to wholeheartedly agree with me. He confirmed that 5 roubles per desk was far from excessive and recalled that the school council had indeed debated this issue. He acknowledged that a serious error had been made and advised me not to take it personally but to forgive the council, as they had likely assumed the desks were unfit for use.

I retorted, ‘How could they think I would accept or purchase desks that were unfit for use!?’

The bishop then turned to Leisman and the dean, asking if either of them had ever inspected the desks. Both admitted they had not. The bishop reprimanded them, saying, ‘How could you pass judgment on the desks without ever having seen them?’ He went on to validate my explanation, stating that it makes no sense to claim that a used desk cannot fetch the price of a new one. A used desk can sometimes be worth many times more than a new one if it is of higher quality, and the bishop concluded that the school council’s decision had been baseless.

Leisman tried to defend himself but only made things worse. He said, ‘Here, the materials are cheaper than in Haapsalu.’

Me: ‘That’s false. We buy the wood from Haapsalu, and with transportation costs, it’s even more expensive.’

Leismann: ‘Rönnkwist was supposed to provide the school desks for free. Why purchase them at all?’

The bishop: ‘That makes no sense! Rönnkwist offered the desks for free when the school was in his building. What right do you have to demand desks from him now that the school is no longer on his property?’

In frustration, Leisman turned to me and spat out, ‘There were only 6 or 7 students in the Fällarna school even when you were a teacher there.’

Me: ‘That is a complete falsehood, and you reported it incorrectly to the Riga school council. Surely you still remember having to resolve this matter before Archbishop Arsenii in Virtsu! Where did you even get such a false figure when you hadn’t even set foot in Fällarna school for three years?’

Leisman turned red as a lobster. This public exposure of his deceit and animosity towards me left him fumbling for words. The bishop, seeing enough, interjected, ‘Leave the old scores behind,’ and with that, the matter was closed.

The bishop, however, seemed genuinely pleased with the ‘sauna’ [34] that I gave to the high-ranking consistory member Leisman and the dean. It was clear to him how unjustly the consistory and school council often acted, as well as how [unjustly] the deans carried out their duties. The bishop, while often unable to intervene in cases where the victims cannot defend themselves, where they suffer from the injustices of the consistory, the school council, and deans, appeared to appreciate my boldness in publicly exposing these injustices.

The bishop also now fully understood the reasons why my superiors are against me, as he clearly saw that Leisman, the main director and mediator of our affairs in the school council and consistory, is my sworn enemy. However, this ‘sauna’ only stoked Leisman’s vengeful fury to the most intense flame. Being a spineless lackey of Leisman, the dean will undoubtedly do everything in his power to have me removed.

Archpriest Nikolai Leisman and his family (EAA.5410.1.53.70)

But all of this is nothing more than a fool’s charade and childish antics. They cannot harm me in any meaningful way. The more they target me, the more they force me to clarify issues and demonstrate honest diligence, which ultimately benefits me. I have nothing to lose except the senseless servitude of a negro that I have longed to escape for some time, but, on the other hand, I have much to gain if only I have life, health, and energy left.

Leisman, in his fury, was reportedly digging through the school journal and other records, trying to find grounds against me. We’ll see what he has managed to unearth!

After this battle, the bishop inspected the school cupboard, the collection of textbooks, and journals. As we were leaving the classroom, an old Lutheran woman approached the bishop, asking for money. She explained that she had been ill for a long time and was now in dire need. The bishop instructed Leisman to give her 3 roubles. It later came to light that this was stupid Agneta’s mother from Hullo, who had previously accused Kreek, the manor steward [35], of striking her while she was working in the manor fields. She claimed to have fallen ill as a result, and the court fined Kreek 10 roubles for the alleged assault.

From the northern side of the classroom, the bishop went to inspect the sacristans’ apartments. He first visited Spuhl’s quarters and blessed Spuhl’s family. From there, he went to see Kreek’s apartment, where the back room was still without wallpaper. Kreek himself was not present. The bishop even wanted to inspect the attic, but I managed to steer him away from the idea. He was curious to the point of nosiness, examining every corner and crevice like a gossipy old woman, even peering into Kreek’s pantry window.

When we came downstairs, we proceeded to my garden. The currant bushes and shrubs were adorned with the most beautiful ripe berries, and everything was lush and vibrant after the refreshing rain. The pond, surrounded by greenery, looked like a picturesque vase with a stunning bouquet.

As we entered through the well gate, and the entire captivating view unfolded, even Leisman, despite his simmering resentment, couldn’t suppress his admiration. He whispered to the dean behind me, ‘Oh, how beautiful!’

There were many Sunday school teachers and other people in the garden. I first guided the bishop to the pond and, in response to his questions, explained its construction, cost, and purpose. From the pond, we walked past the kitchen steps towards the orchard. I wanted to show him the trees I had grafted earlier this spring. However, as the view was not clear from there, I led the bishop to the path by the east side of the garden. From that vantage point, the east-facing orchard beds and the grafts on the other trees were clearly visible. I explained to the bishop the principles of our grafting process, where we order the rootstocks and scions, etc., etc.

Upon returning, the bishop admired the flower beds near the main staircase and around. He then appeared tired and expressed a desire to go inside. The weather was exceptionally beautiful: after the rain, the sun shone brightly, the air was incredibly fresh and invigorating, and there was no wind at all. This weather, combined with the paradisiacal, oasis-like freshness and beauty of my garden amidst the barren landscape, seemed to have a heady, uplifting effect on the bishop. He was noticeably cheerful, bright-eyed, and full of good spirits.

He was particularly taken by the bush currants, laden with their red and yellow clusters of berries, and the prominent gooseberry bush near the path by the pond, which bore four pints of the most magnificent, large berries. At the main staircase, Helena met the bishop, and we both received his blessing. I then escorted the bishop to his new study, which had been set up entirely for his comfort: my new writing desk, a comfortable armchair, a washbasin with water and two towels, etc. My ordination certificate and a government holiday chart were hung on the wall, along with an enlarged portrait of myself made in Paris, displayed above the simple writing desk. The adjoining sleeping room and the school-facing doors were adorned with new, elegant curtains. All of this, combined with the tasteful pictures and the bookshelf, made the room extraordinarily striking.

After settling the bishop in the room, I requested his permission to leave him alone, as bishops typically rest in the rooms prepared for them after inspections. This is when they wash, change into fresh clothes if they have sweated, etc. From the new study, I went directly to the old study, where all the church records had been laid out on the table for inspection. There, I found Leisman and the dean already examining the books. When I enquired if I was needed there, they replied that I was not, though I might be required by the bishop. I returned and found the bishop already seated on the sofa in the parlour. At that moment, the district chief Greshishchev and his junior assistant also joined us.

I continued discussing the issue of Vormsi sectarians with the bishop, explaining how we visit the villages to give stern speeches to people who are abstaining from communion. During this conversation, I presented a book entitled En kort förklaring öfver några af Daniels och Johannes’ syner som hänwisa till Kristi andra ankomat. Af J. N. Matteson [36]. I explained the imagery and highlighted the nihilistic teachings this book imparts to the common folk.

This conversation in the parlour continued until lunch was ready. I then invited the bishop, Leisman, the dean, and the other guests to the meal. The bishop’s entourage on this occasion was small, consisting of the following: Leismann, the dean, a deacon, and the cell-attendant Grierson [37] from the clergy; and, from secular people, the Haapsalu district chief Greshishchev, his junior assistant Kotevnikov, and the coastguard commander Lieutenant Colonel Melgunov (both he and Kotevnikov came from Hiiumaa). Also, Kremnikov was here, so in total there were eight guests seated at the table.

The officer Czajkowski [38] had also been at the church but assumed the bishop would visit him at his home and so returned there to prepare. The Nordgrens were also invited, but the women in their household were reportedly unwell, so none of them could attend.

The cell-attendant dined in the old study. The bishop sat at the southern end of the table in an armchair. Along the eastern side of the table, from south to north, sat Leisman, the dean, and the deacon. Along the western side, from south to north, were Melgunov, Greshishchev, Kotevnikov, and me. At the northern end of the table sat Kremnikov, who entered the room initially flustered and timid but grew more confident after witnessing my calm and open conversation with the bishop.

Serving the guests at the table was Otto Müller, who had worked for many years as a servant for the baron de la Gardie [39] in Haapsalu before moving on to hotel service. He earned a wage of three roubles for the day. Preparing the food was a [text missing]’s woman from Haapsalu, who had been specially brought in yesterday and returned to Haapsalu with the bishop on the steamer today.

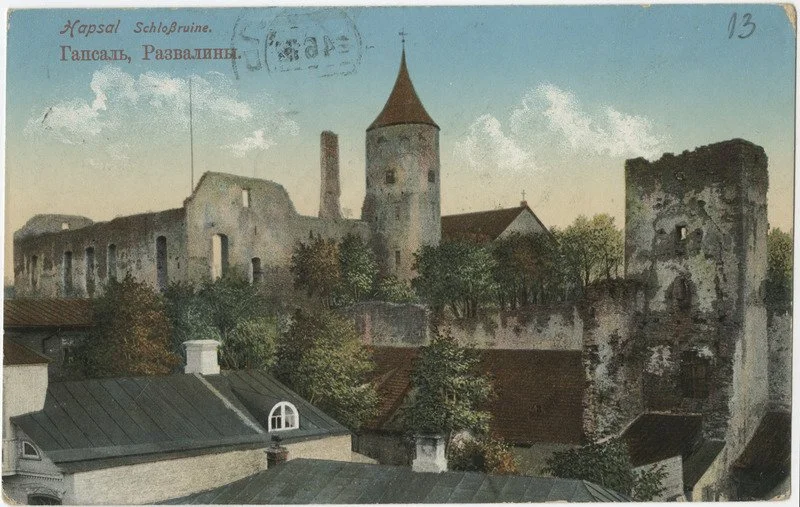

Postcard of Haapsalu castle and houses, early twentieth century

The lunch was extraordinarily lavish: in addition to various warm roasts, pies, puddings, soups, cakes, and other dishes, there were French crayfish, which cost four roubles per box, assorted sardines, herring, cheeses, sausages, porcini mushrooms, confectionery items, and so on. The meal concluded with ice cream. The total cost of the lunch, including all expenses, came to nearly 100 roubles, a sum greater than I spend on my own food for an entire year [40]. Such extravagant expense is indeed the height of absurdity, yet I could not avoid it without risking scandal.

However, I did demonstrate my character and liberal-mindedness in the choice of beverages. Besides pure water and berry syrups mixed with water served in large carafes on the table, I offered no other drinks to my guests. This decision, though regarded as a major mistake and a display of audacious defiance against modern customs, was one I stood by firmly. Even other temperance advocates would not dare to host even ordinary guests without providing intoxicating beverages. Yet here I was, a simple priest, defying centuries of ingrained traditions by serving neither wine nor spirits to a bishop and his esteemed companions.

The dean was visibly startled when I informed him on the nineteenth in Haapsalu that there would be no alcoholic beverages at my lunch today. He advised me against this, warning that I would be labelled a vulgarian for such behaviour. The dean was certain I would change my mind out of fear and that he would find wine and other drinks at my table today. But I am not easily intimidated when I have decided on something, and so I remained steadfast in my resolve to not yield to such absurd customs, regardless of the consequences.

As the guests settled at the table and began eating, their faces displayed a mix of astonishment and disbelief. It was as if they were foxes at a crane’s banquet or cranes at a fox’s [41], completely bewildered by the abrupt break from tradition. The expressions of the dean and Leisman were particularly telling, half startled and half paralysed by the boldness of my decision. They seemed to brace themselves for what might come next after such an audacious move.

I, however, carried myself with an air of complete composure, as if there was nothing unusual about the situation. This demonstrated to all present, regardless of their rank or status, just how petty they seemed before me. My demeanour alleviated the bishop’s discomfort, as others must have initially considered my boldness an affront, and the bishop immediately began conversing warmly and enthusiastically with me, saying:

‘Please, sit down as well. I am sure you will find something suitable for yourself on the table, as I’ve heard you are a strict vegetarian’ [42].

And so a conversation about vegetarianism began between the bishop and me. After some time discussing, and seeing that the other guests - especially Leisman and the dean - were beginning to recover from their initial shock, I offered an explanation as to why I had chosen not to serve intoxicating drinks at this gathering. I made it clear that the clergy of the Orthodox Church and the Russian people have a poor reputation due to drinking habits. By taking this stance, I aimed to improve this perception, if not further, then at least on Vormsi. I emphasised that I intended to lead by example, not merely with words. This public statement was yet another unexpected blow to the guests, and the dean and Leisman seemed ready to sink into the ground.

The bishop now found himself caught between two fires. Though I had carefully framed my statement to show that I sought to protect, not harm, the honour of the clergy and the Russian people, the truth was hard to conceal. The well-known issue of excessive drinking among the clergy and Russian populace hit everyone present deeply. I allowed the weight of this truth to linger and left it to the bishop to navigate the situation.

The bishop, realising that I stood firmly for the truth without fear, avoided engaging in direct opposition to my stance. At the same time, he had to maintain appearances by defending the clergy and the Russian people, especially since all the guests at the table were Russians, aside from Leisman, who is Estonian, and avid drinkers. Thus, he commended my commitment to temperance, expressing his approval and even delight at being offered a completely temperate lunch. Then he attempted to walk a fine line between truth and justification, relying on scripture and other arguments to downplay the matter. He showed that moderate drinking is not inherently sinful, that the state and Russian temperance societies advocate moderation rather than abstinence [43], and that people cannot live without some form of stimulant, because otherwise the state could make vodka disappear, etc., and if vodka was abolished, it would likely be replaced by tobacco and then by opium due to humanity’s flawed nature.

The Vormsi Orthodox parochial house (ironically enough given Vaarask’s teetotalism, today a pub)

To avoid embarrassing the bishop further and to deny Leisman any grounds for complaints about me to the higher authorities, I wisely refrained from harsh debate on the matter. Instead, I pointed out that moderation lacks any clear boundaries, rendering it ineffective. I also argued that the clergy cannot rightly admonish others for sins they themselves indulge in, as doing so invites ridicule, much like the [Lutheran] pastors who have long been mocked with the saying, ‘Do as I say, not as I do.’ The bishop was visibly relieved that I did not push him into further discomfort and conceded the validity of my arguments. I then steered the conversation toward official matters, posing a series of practical questions to the bishop.

We addressed issues such as whether it is permissible to use force to bring stubborn Orthodox believers to a priest to resolve disputes and force those who have not taken communion in years to fulfil their religious obligations with the help of police [44]. The bishop explained that such actions are permissible if the matter is formally presented to the governor through the consistory. Several other administrative matters were also resolved.

I then explained to the bishop the foundational principles that underpin the strength of the new sects: their alignment with the people’s mindset and demands, their complete freedom in preaching and publishing, their liberation of the common people from hierarchical authority in religious matters, their appeal to freedom in secular matters, their use of universally popular songs, and the state’s failure to understand the true aims and tactics of the sects, which grants them unrestrained freedom, etc.

Then I steered the conversation toward literature, emphasising the importance of diligently spreading Orthodox literature to compete with publications from other faiths. I argued that it is crucial to publish a newspaper in Estonian and Latvian for the Orthodox faith [45], as currently all the Baltic press, except for Russian-language publications, is dominated by Lutheran ideology. I explained that without this effort, Estonian, Latvian, and Swedish Orthodox Christians in the Baltic region would inevitably grow up influenced by Lutheran or sectarian ideologies, as they lack Orthodox literature to counteract these influences and would accept the opposing views presented in other publications as true.

The bishop acknowledged that adherents of other faiths are wealthy and capable of producing affordable literature, while our resources for such initiatives are limited. Eventually, the conversation turned to the Vormsi manor [46]. I highlighted how Hunnius had let the manor buildings, park, garden, and other assets deteriorate, exploiting the estate mercilessly. Melgunov, Greshishchev, and Kremnikov confirmed my observations, and the bishop added that he was aware that Andrevskii and others had expressed interest in purchasing the Vormsi manor. However, the question of placing the manor under the jurisdiction of the Riga monastery [47] was still under discussion, which was why the bishop intended to inspect the manor later that day.

Ruins of Magnushof manor

Thus, many important issues were addressed during the meal, with lively and productive discussions throughout. Despite the lack of alcohol, the lunch was anything but dull, unlike those meals where intoxicating beverages dominate. The bishop and I spent the entire meal deeply engaged in conversation, looking directly at each other. Kotevnikov, seated directly in our line of sight, unintentionally forced us to lean slightly to either side to maintain our connection. The other diners, however, barely participated in the conversation, interjecting only occasionally toward the end when the discussion turned to the manor.

Before lunch, I felt energetic, but at the lunch table I was already feeling utterly fatigued. The combined strain of heavy preparations and my worsening cold made it difficult to sustain the thread of conversation. My explanations were becoming sluggish, and it was a challenge to keep my thoughts clear. Nevertheless, I managed to carry the conversation through to the end without major setbacks. Although I did not eat anything myself, the guests were served an abundance of dishes, many of which remained untouched by the end of the meal.

When we sat down to eat, everyone made only the sign of the cross, but upon rising from the table, each guest went to the bishop for his blessing. The bishop also thanked both Helena and me for the meal. Afterward, the dean and Leisman returned to the old study to continue reviewing church records, while I remained with the bishop in the parlour.

The bishop began sampling currants, strawberries, and raspberries from the fruit vase on the parlour table, strolling around the room, and gazing out the window. From there, he could see the standard bushes and a variety of other plants that seemed to pique his interest.

He once again brought up gardening and various other topics, but soon began glancing at the clock more frequently as time pressed on. At this point, the dean entered the room, drew the bishop aside from me, and whispered, ‘Would it be possible to have him in front of us?’ [48]. The bishop, however, waved him off with a dismissive gesture and said firmly, ‘No need!’ The dean retreated as if he had been scolded, like a dog with its tail tucked between its legs, and slinked back to the old study. The bishop and I resumed our conversation as before.

Leisman, who has spent years slandering me and my work to the bishop, had come with the apparent intent of delivering a decisive blow against me. He likely believed this visit would seal my downfall. Instead, things unfolded in quite the opposite way: Leisman, along with his henchman and agent, the dean Bezhanitskii, found themselves utterly outmatched. During the inspection, they had been publicly rebuked and outmanoeuvred by me in front of the bishop.

Now they seemed to gather their remaining courage and attempted one last ploy: demanding that Kreek be examined, hoping to expose my perceived failures in managing him. There had been much contention between me, Leisman, and the school board regarding Kreek, and they sought to use his examination as a pretext to discredit me. However, the bishop, who had already discerned their Jesuit-like schemes and wanted to maintain his good mood during the visit (given how impressed he had been with the furnishings, organisation, and overall state of affairs), immediately dismissed their request. With that, their final attempt to undermine me fell flat.

Konstantin Kreek (Orthodox sacristan and schoolmaster on Vormsi) with his wife Maria, early 1900s (EAA.5410.1.51.43)

The frustration boiling within Leisman, especially after witnessing even the dean return with nothing more than a long face, was evident. After some further discussion on various matters, the bishop turned to me and asked, ‘Well, how is your record-keeping?’

Me: ‘I cannot say much about it myself. Leisman and the dean have reviewed the books. You should ask them.’ Right on cue, the dean entered the room, and when the bishop posed the question to him, he answered, ‘Everything is in perfect order, one could even say in exemplary order.’ Thus, even by the dean’s own admission, there was no fault to be found in the church’s records that could be used against me. It remains to be seen, however, what Leisman might later try to allege.

With this acknowledgment from the dean, the bishop thanked me, praising the well-kept state of affairs, and then began preparing to leave. I asked for permission to accompany him and show him the manor. The bishop replied, ‘Only if it doesn’t burden you, I do not wish to trouble you any further.’

The dean, acting like an excitable child, asked if he might take some berries from the dish for the road, which was done, and he seemed delighted at this small gesture.

Once the bishop had been escorted to the stairs, I grabbed my hat and headed to the main gate, where the bishop boarded Nordgren’s carriage, drawn by three horses. Leisman and the dean rode together in the manor’s carriage, pulled by two horses. Greshishchev and Kotevnikov rode in the manor’s charabanc [49], while Melgunov followed in Nordgren’s charabanc. I took my small cart and horse, accompanying the procession to the manor.

At the rear of the procession, following me, Kremnikov rode with his son and others in light carts. Kremnikov hurried home to be the first to telephone from Vormsi to Haapsalu, specifically to report the bishop’s departure time. Amid the rush, Lars had forgotten to place the apron and cushion on my cart, and the municipal official brought these to me in his own cart while we were traveling through the Hullo meadow.

A bit further along, my charabanc’s left rear wheel locked up, likely over-screwed during greasing. Despite this, I was forced to continue at a hurried pace, racing along the muddy, stony road to keep up with the others, who were speeding along in their carriages. Miraculously, I arrived at the manor just as the bishop stepped out of his carriage.

The bishop and his entourage first ascended to the upper floor of the manor, which was inspected thoroughly. The old Wunderlich, serving as the manor’s police representative, was present to welcome the group. He claimed that the doors on the lower floor were locked and that the manor steward was not at home. The bishop expressed an interest in walking on the large balcony near the greenhouse, but I stopped him in time, fearing he might fall through.

From the windows of the upper floor, I showed the bishop the manor’s fields and explained the overall size of the estate, mentioning that portions of it were allocated to peasants and others, with 900 desiatins [50] projected for the monastery. Upon descending from the upper floor, we again pressed Wunderlich to open the doors on the lower level. He maintained that they were nailed shut, but I publicly refuted this absurd claim, pointing out that workers lived inside, so it was impossible for the doors to be nailed shut; so, I urged the district chief to demand the doors be opened, which he promptly did, and soon the manor warden’s quarters were unlocked for inspection. We entered but avoided venturing further due to fears of the ceiling collapsing.

Afterward, we explored the garden, where the bishop, full of energy like a youthful boy, wandered through the tall grass toward the greenhouse to admire the apricot trees. When we reached the lilac-lined path leading to the greenhouse, the bishop checked his watch and immediately decided to depart, worried about being late for Vespers in Haapsalu. Thus, much of the larger, more beautiful garden went unvisited. He repeatedly lamented the disorder he observed at the manor, acknowledging that my descriptions during lunch had not been exaggerated.

While at the manor, the municipal official managed to loosen the stuck wheel on my cart, but it locked up again as I approached the Förby forest. The official tried to fix it a second time but failed, forcing me to race down the rough road with the jammed wheel to catch up with the others, who were more than a verst [51] ahead. Though I feared the cart might break down and leave me stranded, I managed to rejoin the bishop’s procession near the cordon checkpoint [52].

At the cordon, the bishop stepped out of his carriage to bless the soldiers standing in formation. He briefly spoke with the officer [Czajkowski] before continuing on foot toward the pier. At the pier, he stood near the launch and spoke with me for about 15 minutes, seemingly forgetting his earlier concerns about being late. Meanwhile, the rest of the group appeared restless and anxious, with Leisman visibly envious.

The bishop thanked me multiple times, offering his blessing three times in parting. He kept restarting the conversation as if he was genuinely reluctant to leave. He commended my diligence and the exceptional upkeep of the parish, remarking that such effort could not go unrewarded. He encouraged me to steadfastly endure the challenges of Vormsi’s isolated life, etc., etc.

As the bishop boarded the launch, the cook tried to join as well, but the dean initially refused to let her. I intervened, insisting she be allowed aboard. The district chief enquired if the bishop objected to her presence, to which the bishop replied, ‘Not at all.’ Thus, with determination, I managed to have the cook accompany the bishop. Otherwise, she would have had to travel from Förby to Söderby and from there to Haapsalu.

Kreek’s and Spuhl’s Vladimirs [53] also accompanied the bishop to Haapsalu. Melgunov, Kotevnikov, the officer, and I stood on the harbour pier until the bishop’s launch carried him far into the distance. The weather was exceptionally beautiful: clear and calm.

Harbour of Sviby, Vormsi

From the harbour, we all proceeded to the officer’s house, where we had tea and talked for a while. Both Kotevnikov and Melgunov remarked that they had never seen the bishop in such good spirits as he was today, saying that everything about his visit here had greatly pleased him. They complimented me on today with ‘good show,’ and the officer congratulated me on a potential future promotion, adding that he had personally overheard the bishop say, ‘Your diligence and excellent management will not go unrewarded’, etc.

In Pühalepa [54], they said, the bishop had been displeased. Põrk [55] had lost his composure, stammered, but later recovered. When Melgunov and Kotevnikov departed for Hiiumaa, I stayed behind to chat further with the Czajkowskis and Kremnikow’s daughter before setting off for home. Soldiers managed to loosen my cart wheel again, but after only a short distance from the cordon, it seized up once more. I had to continue to the manor’s forge, where the blacksmith Marr along with the overseer struggled to release the wheel. There, I also discussed the meadow with the manor steward. The wheel caused no further trouble on the way home.

Upon arriving home, I inspected the garden with young Kalf. Inside, we had tea together with Kalf, Miss Neumann, Kimberg’s wife and children, the Spuhls, and Kreek. These guests, along with Kimberg, had eaten lunch at our home after the bishop’s departure, as Neumann and Kimberg’s wife had been helping all day. It was my first meal of the day. After tea, we spent some time chatting in the drawing room. Once the guests had left, I spoke with the sacristans. After they departed, I ate once more and then had a long conversation with Helena and Liisa. It was not until 2 a.m. that we finally went to bed.

Thus, we have received the governor [56], Prince Meshcherskii and his wife [57], and the bishop. Hosting the first two was a minor matter, but the bishop’s reception truly exhausted us. Helena said she felt her heart would burst when the dean arrived at the church in the morning and insisted the lunch had to be hastened. She ran back home from the church to inform the cooks and then rushed back again to be present for the bishop’s arrival. It is daunting to look back on how much effort and mental strain went into the preparations, all for just a few hours of the bishop’s presence. He was here for only about five hours—arriving at the church at 10 a.m. and leaving at 3 p.m.

The hardest part for Helena and me was that neither of us had ever witnessed a bishop’s reception before, nor could we get reliable guidance from anyone else. Yet, despite all this, everything went smoothly, even though I feared I might fail due to my illness. A clear understanding of the situation and confidence in leading often guide one in the absence of prior knowledge, whereas experienced cowards often falter.

Yes, great effort was exerted, significant expenses were incurred, but the fact that everything went well makes it all worthwhile. Additionally, many important matters were resolved during this brief period. The bishop himself was incredibly sympathetic, a very tall and handsome man. I liked him more than Donat [58] and Arsenii. Onward with determination from this significant day!

Notes

[1] Some translated sources relating to the 1886 conversion can be found here: https://www.balticorthodoxy.com/swedish-conversions

[2] For Agafangel’s activities in Riga diocese, see A. V. Gavrilin, ‘Rizhskii period sluzheniia sviashchennoispovednika mitropolita Agafangela’, Vestnik PSTGU: II. Istoriia. Istoriia Russkoi pravoslavnoi tserkvi, no. 1 (2005): 47–61.

[3] Jaan Spuhl (1859-1916), Jakob Vaarask’s brother-in-law, Orthodox sacristan, schoolteacher, and intellectual: also known under the nom de plume Jaan Spuhl-Rotalia.

[4] A small community of Estonian traders and settlers was also present on the island.

[5] Helena Vaarask, Jakob’s wife (1868 - early 1940s); Juula Spuhl, Spuhl’s wife; Jaan Lobjakas (1870-1945), Vormsi police officer.

[6] We have left Vaarask’s spelling of Swedish names unamended.

[7] Royal gate – the central doors in the iconostasis.

[8] Konstantin Kreek (1852-1916), Orthodox sacristan and schoolteacher. Kreek had several sons, including the future Estonian composer Cyrillus Kreek.

[9] Chronicle – an annual record of notable events in the parish; liturgical journal – a record of all liturgies and sermons conducted in the church.

[10] Haapsalu is the closest mainland town to the island of Vormsi: in the late Russian Empire, it was best known as a spa town frequented by the imperial family and other celebrities, such as the composer Petr Tchaikovskii.

[11] Julius Alexander Nordgren (1836-1923), the Lutheran pastor on Vormsi from 1870 to 1902.

[12] A medal issued in 1896 to clergy and officials on active service during the reign of Alexander III (1881-1894).

[13] The dean here was Father Aleksandr Bezhanitskii (1858-1926): he was dean of Haapsalu from 1898 to 1907. Some details regarding his family life can be found here: https://www.balticorthodoxy.com/stefan-bezhanitskii

[14] Aër – a large cloth covering the paten and chalice used during communion to convey wafers and wine, the body and blood of Christ.

[15] Archpriest Nikolai Leisman (1862-1947) had previously been the dean of Haapsalu from 1888 to 1896: he then moved to a parish in Riga and served as a member of the Riga diocesan consistory from 1900 to 1915. In 1933, he became Archbishop Nikolai (Leisman) of Pechory.

[16] Ambon – the raised part of an Orthodox church interior directly in front of the iconostasis and the altar.

[17] The Dismissal – the final blessing at the end of the liturgy.

[18] Old Church Slavonic – the medieval liturgical language of the Russian Orthodox Church.

[19] Many Years – a blessing calling for the long life (‘many years’) of political leaders, the senior clergy, the parish as a collective, individual parishioners, and all the Orthodox faithful. Also known as the polychronion.

[20] By ‘sectarian’, Vaarask means here Evangelical Christian groups: some of these were Baptists, while others were followers of the Swedish missionary Lars Johan Österblom (1837-1932), active on Vormsi between 1873 and 1888.

[21] A Baptist community was established on Vormsi in 1884, although it had no permanent pastor until the early 1900s. While the Russian Baptist movement had been made illegal in the Russian Empire from 1894, Baptist groups with non-Russian memberships remained legal.

[22] Archbishop Arsenii (Briantsev) (1839-1914), prelate of Riga from 1887 to 1897.

[23] During the ‘russification’ of the Baltic provinces in the 1880s, Russian was made the obligatory language of instruction in schools. In practice, however, native languages continued to be used.

[24] Surviving transcriptions of Vaarask’s sermons do indeed indicate he was an eloquent and charismatic speaker capable of discoursing at length.

[25] Churchwarden – a member of the laity who assists in maintaining the church and parish buildings.

[26] The Vormsi Orthodox church of the Ascension was sanctified in 1890: a distinctive red-brick building complete with onion domes, the church’s ruins still stand near the village of Hullo.

[27] Saaremaa, Muhu, and Hiiumaa are three large islands to the south and east of Vormsi.

[28] Phelonion – a sleeveless cloak worn on over the rest of a priest’s vestments.

[29] Rites – the clergy usually travelled around their parishes to perform prayer services and rites like extreme unction in people’s homes.

[30] Father Nikolai Orlov (1834-1897), first Orthodox priest of Vormsi from 1886 to 1895.

[31] Spuhl’s experiments in pomology on Vormsi, performed together with Vaarask and Kreek, are still known today in Estonian horticulture.

[32] For more about Orthodox schooling on Vormsi, see https://www.balticorthodoxy.com/school

[33] School council – the council in charge of the Riga school district, a branch of the Ministry of Education that oversaw all primary schooling in the Baltic provinces.

[34] The literal translation of Vaarask’s term: ‘roasting’ may convey the meaning better.

[35] This is a different Kreek to the sacristan Konstantin Kreek.

[36] Swedish: A Brief Explanation of Some of the Visions of Daniel and John Which Refer to the Second Coming of Christ. By J. N. Matteson.

[37] Cell-attendant (keleinik) - a servant (usually a monk) who attends on a bishop or an abbot.

[38] As noted earlier in Vaarask’s diaries, Czajkowski, the senior officer in charge of the Vormsi infantry unit, was a Polish Catholic.

[39] The de la Gardie family in Haapsalu descended from a seventeenth-century Swedish ancestor who purchased the town’s medieval castle: the branch of the family in the Russian Empire was a cadet branch.

[40] To put this sum into context, Vaarask earnt 1,300 roubles a year as an Orthodox priest in the Baltic provinces.

[41] The English equivalent of this idiom would be ‘a fish out of water’.

[42] Vaarask became a vegetarian on 19 June 1891.

[43] The large temperance societies run by the Russian state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did indeed urge moderation rather than abstinence, a fact repeatedly condemned by teetotallers as hypocritical and useless.

[44] In the Russian Empire, all Orthodox believers were obliged by law to attend confession and communion at least once a year.

[45] The Latvian Orthodox newspaper Pareizticīgo Latviešu Vēstnesis (Latvian Orthodox Herald) started running only from 1906, while its Estonian equivalent Usk ja Elu (Faith and Life) was issued from 1908.

[46] The Vormsi manor was Magnushof, today in ruins. Like the rest of Vormsi, Magnushof had been owned from the eighteenth century by the Stackelberg family, aristocratic Baltic Germans. However, with the death of Baron Otto Friedrich Fromhold von Stackelberg in 1887, the family sold the manor and the island to the Russian state in 1894.

[47] The Riga Orthodox monastery of St Alexios, founded in 1896.

[48] ‘Would it be possible to have him in front of us?’ – the dean is proposing to subject Vaarask to a disciplinary hearing.

[49] A long horse-drawn cart with two or more benches.

[50] Desiatina – imperial Russian unit of land measurement equivalent to 1.09 hectares.

[51] Versta – imperial Russian unit of distance equivalent to 1.067 kilometres.

[52] Cordon checkpoint – a customs post used by the coastguard to prevent smuggling.

[53] The sons of Kreek and Spuhl, both named Vladimir/Voldemar.

[54] Pühalepa is a village on the island of Hiiumaa: an Orthodox parish was created there in 1884.

[55] Father Mihkel Põrk (1860-1940), priest of the parish of Pühalepa from 1896 to 1904.

[56] Evstafii Skalon (1845-1902), governor of Estland province from 1894 to 1902, visited Vormsi on 11 August 1896.

[57] Prince Meshcherskii was a representative of the Estland branch of the Ministry of State Property, which managed the Magnushof estate after its purchase in 1894: Meshcherskii visited Vormsi on 29-30 June 1897.

[58] Bishop Donat (Babinskii-Sokolov) (1828-1896), prelate of Riga from 1882 to 1887.

Source

EAA.2288.1.45.154-168ob.

Translator

Albert Ludwig Roine

Preface and notes

James M. White

Date added

28 January 2026