Mission

Orthodox Mission in Late Imperial Riga Diocese

The Russian Empire was one of the most religiously diverse polities to have ever existed. Across its vast interiors and along its lengthy borders were millions of non-Orthodox, some belonging to well-organised and recognised faiths (Catholicism, Lutheranism, Islam, Buddhism), others adhering to a whole panoply of polytheist, schismatic, and sectarian groups whose forms of veneration could range from the benign (nature worship, pacificism, vegetarianism) to the extreme, such as denying the legitimacy of the tsar and bodily mutilation. The Russian Orthodox Church felt at least some duty to convert these peoples to what it regarded as the one true faith, and as the empire’s state Church it enjoyed benefits to help it do so, not least a monopoly on missionary activities.

Clergy in front of a church of the Altai mission: founded in the late 1830s, the mission’s aim was to convert the polytheist peoples of the Altai (western Siberia) to Orthodoxy

However, it was only in the second half of the nineteenth century that an organised missionary movement coagulated, with the job of proselytising in part removed from the hands of parish priests and placed into those of professional missionaries. Such a vocation was certainly not an easy one. Target villages could be tens or even hundreds of kilometres from major towns, meaning tedious trips either by cart along bumpy, near-derelict tracks or on foot through snow and sleet, rain and mud, heat and dust. A cordial reception was by no means guaranteed. The local priest would have no particular reason to proffer friendship, potentially regarding the missionary as upstart competition in a parish where the clergyman himself had been resident for years, perhaps decades. Non-Orthodox villagers were accustomed to looking askance at any representative of the state Church, not least because their faiths were often either semi-legal or completely illegal in the empire’s punitive law code. Their officiants were experts at evading debates with missionaries, partially as a means of wasting time and making their opponents look ridiculous.

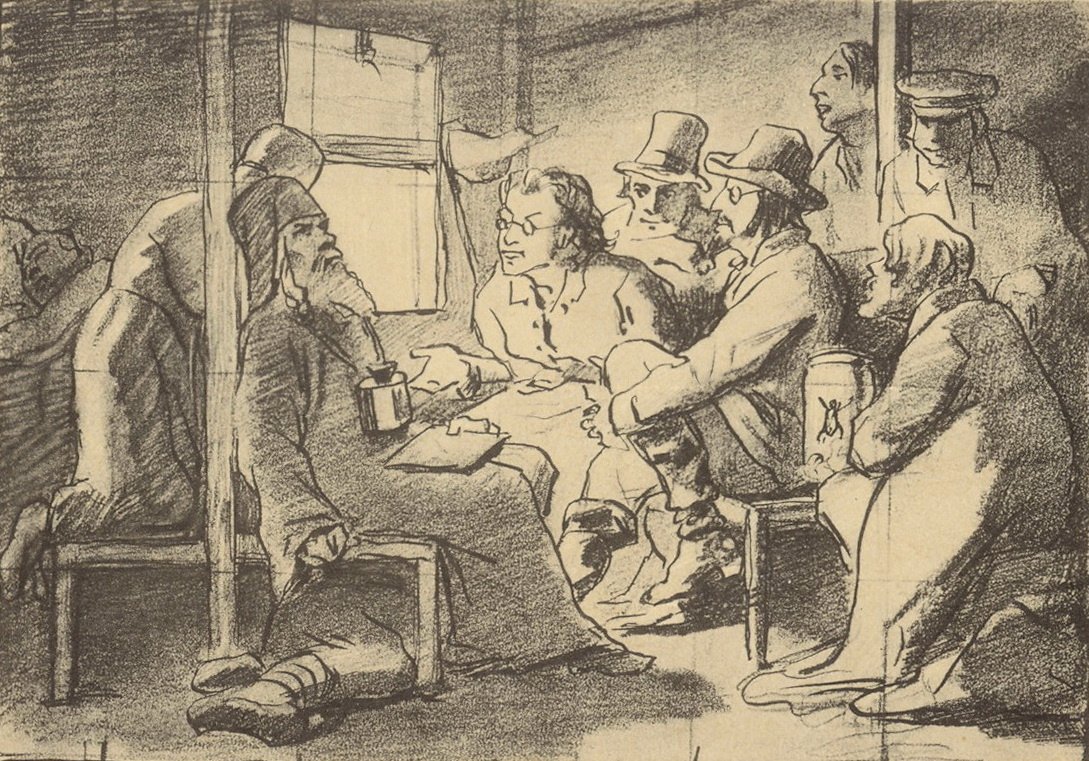

Dmitrii Zhukov, An Argument about Faith (1867)

Even when work could begin, it typically revolved around open-air sermons and disputes in smoky peasant huts, fully sealed in the winter to keep the warmth in and the cold out (and missionary work often took place during this season, since peasants were busy throughout the rest of the year with their fields and farm animals). Here, the missionary’s highly formalised book knowledge, obtained through years of study in prestigious schools and centres of learning, collided with the living faith of the people, a mish-mash of half-digested sermons, rote-learned Scripture, folklore, and rigid ritual observances. The missionary might have to struggle to appeal to even his own co-religionists, let alone those he (missionaries were mostly men) had to persuade, convince, and ultimately convert. And while the compensation for this toil was high, this wealth might have only widened the gulf between the missionaries and their poor, uneducated interlocutors [1].

Little wonder, then, that some missionaries found it easier to resort to police assistance, summoning the repressive hand of the state to strike down their opponents. This accounts for the poor reputation imperial Orthodox missionaries enjoyed: even some churchmen were aghast at their coercive tactics, while those outside the Church often saw them as agents of government reaction [2]. Modern historians have been no kinder, depicting missionaries as men who promulgated an inflexible definition of Orthodox behaviour and exacerbated social division at a time when the Russian Empire could have benefited from more unity [3].

Vasilii Perov, An Argument about Faith (in a Train Carriage) (1880)

How did the Orthodox mission look in the Baltic provinces? Here, the Orthodox Church confronted three principal opponents: Lutheranism (the traditional faith of the Baltic region), Old Belief (a catch-all term denoting those opposed to ritual reforms undertaken in the Orthodox Church in the mid-seventeenth century), and so-called ‘sectarianism’ (Evangelical Christians, such as Baptists, Adventists, and Methodists). Compared to the Lutherans and the Old Believers at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Orthodox were very much a minority, confined mostly to Russian settler populations.

The mission was thus baked into the very foundation stones of Baltic Orthodoxy. The suffragan diocese of Riga was created in 1836 as the local embodiment of Nicholas I’s severe persecution of Old Belief (which had a strong presence in the region’s cities and areas like the western coast of Lake Peipus/Chudskoe), wherein Old Believer prayer houses were closed, leaders were exiled, and property confiscated. In 1850, the Riga suffragancy became an independent diocese so that it could handle the conversion from Lutheranism to Orthodoxy of around 110,000 Estonian and Latvian peasants (although this movement owed little, if anything, to Orthodox missionary intervention). A further mass conversion, centred on western Estland province, occurred in 1880s, with around 15,000 Lutherans joining the Orthodox Church. By 1914, there were 273,023 Orthodox in the diocese (Russians, Estonians, Latvians, and Swedes) and 210 parishes [4]. But, despite this growth, Orthodoxy was a distinct minority in all the Baltic provinces: 9.23% of the population in Estland, 15.58% in Livland, and 5.02% in Kurland [5]. At the turn of the century, the Old Believers numbered around 25,660, while there were 22,268 members of 173 sectarian communities [6].

Old Believer prayer house in Kallaste, Estonia, 1923 (EFA.554.0.187045)

Given the diversity of their parishes and the sustained presence of rival officiants, the Orthodox clergy of Riga diocese were always expected to engage in some form of missionary activity. This was especially given that state repression of other faiths waxed and waned. In the 1860s, Alexander II was comparatively lenient on Old Belief and resolved to ignore cases of mass ‘apostasy’ to Lutheranism occurring from the late 1850s to the 1870s, failing to prosecute Lutheran clergy who performed sacraments and other rites for Orthodox converts [7]. An about-face came the accession of his son Alexander III in 1881: in Livland province alone, 129 Lutheran pastors were prosecuted for ‘tempting’ the Orthodox between 1884 and 1892 [8]. At least in some parishes, the Orthodox clergy actively participated in the seizure of sectarian prayer houses and Sunday schools [9].

The relative poverty of Riga diocese (most of the converts in the 1840s and 80s were landless peasants surrounded by an overwhelmingly Lutheran population and Baltic German landlords) made brotherhoods, collaborative associations uniting the clergy with zealous, influential, and wealthy members of the laity, a popular and useful solution for mobilising Orthodox missionary resources. Nine brotherhoods (not to mention the local branches of each brotherhood) were in operation in Riga diocese in 1897 [10], more than in almost any other eparchy [11]. These brotherhoods were mostly engaged in church and school construction, the translation of Orthodox literature into Estonian and Latvian, and, in the 1880s and 90s, the formation of monasteries (of which there were four by the early twentieth century) [12]. Both the Orthodox parish school network and the monasteries were intended to have an indirect missionary purpose: by providing the local population with education, charity, and the beauty of the liturgy, these institutions would supposedly draw Lutherans into Orthodoxy.

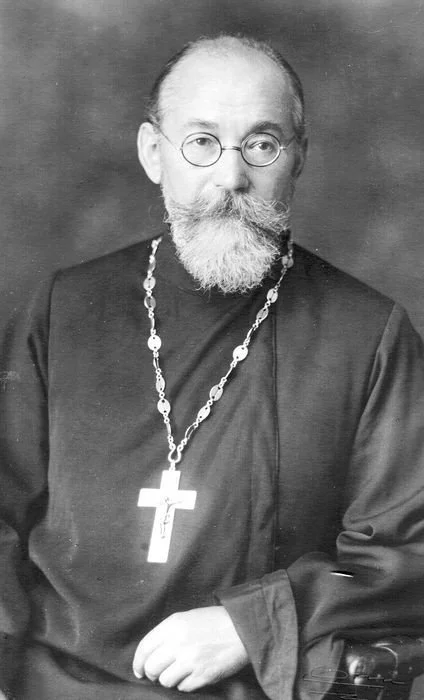

Archpriest Vladimir Pliss, lecturer in ‘anti-schismatic’ studies at the Riga seminary (later chair of the Riga Diocesan Missionary Council)

Otherwise, the diocese remained largely untouched by the Russian Orthodox Church’s efforts to systematise and professionalise the mission. Despite an 1886 instruction for diocesan missionaries to be appointed in every one of the empire’s Orthodox bishoprics, no such individual was hired in Riga, despite some interest in the idea from Bishop Arsenii (Briantsev) [13]: it seems that the cost of professional missionaries was too prohibitive a prospect for the impoverished diocese. With the exception of brotherhoods, missionary institutions in the diocese by the end of the nineteenth century were limited to a library in Riga (containing, among other things, treasured manuscripts seized by the police from the Old Believers) [14], the appointment of a professor of ‘anti-schismatic studies’ at the Orthodox seminary, and regular disputations with Old Believer leaders: these were held in Riga and were initially led by celebrity clergy from outside the Baltics [15].

These fragile beginnings were threatened by momentous changes in 1905. In response to surging violence across the empire during the First Russian Revolution (1905-07), Nicholas II promulgated an edict of religious toleration in April 1905: by abolishing the prohibition on Orthodox believers converting to other faiths and by fully legalising Old Belief, the tsar and his advisors hoped to quell disorder in the borderlands and rally conservative citizens behind the regime. The edict marked a time of soul-searching in the Russian Orthodox Church: bereft of police and legal protections, Orthodox hierarchs and laypeople had to meditate on how to make Orthodoxy more viable in the face of revitalised competition. Riga diocese was no different. 11,408 cases of ‘apostasy’ from Orthodoxy to Lutheranism and Catholicism occurred between 1905 and 1910 [16]. Arguing in 1905 that ‘the Orthodox Church must now realise principles [of toleration] in popular life without either limitations or sponsorship from the side of the government’ [17], Archbishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii) of Riga organised a local church congress to implement progressive reforms.

Elsewhere in the empire, Orthodox missionaries, now well organised and with powerful representatives at the hearts of political and church power, hurried to develop the mission in response to the 1905 edict of toleration. On 20-26 May 1908, the Holy Synod (the Russian Orthodox Church’s leading body) ordered the creation of local missionary councils in all eparchies [18]. But while other dioceses created such missionary councils almost immediately, in Riga there was ambivalence among the clergy. Discussing the Holy Synod’s order in November 1908, a diocesan congress urged that the internal mission should be adapted to local conditions. For them, this meant leaving most aspects of missionary work to parish priests. Appointing diocesan and district missionaries would be useless, they claimed [19].

Despite this hesitancy, on 31 October 1909 Archbishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii) applied for the appointment of two diocesan missionaries, one responsible for Estonians, the other for Latvians. But the Holy Synod penny-pinched, creating a position for only one missionary with a salary of 2,500 roubles a year (almost double the pay assigned to priests in the Baltic provinces) [20]. Appointed on 16 May 1911, the successful applicant was the Estonian Father Joann Pavel (1874-1940), previously the clergyman of Väike-Lähtru [21]. It took another three years before funds were released for a Latvian Orthodox missionary: on 21 January 1914, Teodors Bucens (1869-1942) was given the job [22]. A former Baptist preacher and leader, Bucens had converted to Orthodoxy with his family on 27 December 1913: in other words, Bucens was Orthodox for less than a month before being appointed as a missionary [23]. His tenure was also quite brief, since the German invasion of the Baltic provinces in the summer of 1915 cut off his access to most Latvian-speaking areas. No steps were ever taken to hire a missionary for the diocese’s Russian groups: presumably this was because, as a deanery meeting in 1916 put it, ‘only a few Russians convert from Orthodoxy to Lutheranism. The Russian person is little interested in Lutheranism, the Lutheran church does not draw him’ [24].

Father Joann Pavel (Estonian Orthodox missionary) and his family

While missionaries were being enlisted, the Synod’s 1908 demand for a local missionary council was also realised, since such could act, in the words of a local church congress, ‘as an organ for the unification and development of missionary affairs in the diocese’ [25]. The Riga Diocesan Missionary Council (RDMC) was established on 5 November 1910: chaired by the seminary teacher, church newspaper editor, and experienced anti-Old Believer preacher Archpriest Vladimir Pliss (1862-1927), the RDMC’s board was made up entirely of priests, two Russian, two Latvian, and one Estonian [26]. The next organisational step, made from 1912, was forming local branches of the RDMC. Father Vassili Verlok (1875-1917) was instructed to formulate regulations for a branch on the Estonian island of Hiiumaa, which would then serve as an exemplar for everyone else [27]. This process of establishing local branches and confirming their regulations took several years: the ordinances of the Viljandi branch were still not approved as of 24 November 1916 [28].

This organisational structure was presumably adopted to reflect that of the numerous brotherhoods in Riga diocese and to avoid the cost of hiring district missionaries (in other words, individuals junior to the diocesan missionaries). But it also drew some criticism. Father Jānis Vinters, the dean of Ventspils, complained on 12 March 1912 that the Ventspils branch of the RMDC was entirely stagnant, since three of its Russian members did not speak local languages, the sacristan-members did not have missionary training, and the priest-members lacked both the necessary time and knowledge to hold disputations with rival officiants. Vinters believed that it would be preferable to hire a specialist local missionary [29]. Elsewhere, Father Dmitrii Dubkovskii (1871-1951/52) remonstrated that there were no funds available in his deanery of Haapsalu to support the RDMC branch in his town [30].

Teodors Bucens, Latvian Orthodox missionary (photo from interwar period)

A challenge to the branch structure was also posed by priests in Tallinn. In early 1914, the Orthodox clergy in Estland’s capital expressed aggrievement that the two diocesan missionaries were both based in Riga: they argued that Father Pavel, as the missionary for Estonian parishes, should live in their city. Pavel’s move there, the Tallinn branch of the RDMC proposed on 20 February 1914, would allow for the unification of all missionary matters in Estland province under the aegis of the Tallinn branch [31]. Such intentions were incorporated into the draft regulations for the Tallinn branch, which led to their rejection: perhaps the diocesan bureaucrats in Riga feared that decentralisation in missionary matters would take too much power out of their hands [32].

There was little enthusiasm among the laity for participating in the missionary branches. At its general assembly on 23 October 1912, the Hiiumaa RDMC branch ruled that ‘fresh forces [for the mission] will not be found by the organisation of missionary branches, since finding people useful for missionary affairs amidst local parishioners is almost impossible’ [33]. This claim from the Hiiumaa branch is ironic, given that it was one of the very few that managed to attract members from outside the clergy: as of 4 May 1912, the membership included three priests, six psalmists, four teachers, a local official, and six peasants [34]. Elsewhere, the branches did indeed find it difficult to entice people other than priests, such as those in Ventspils, Tallinn, Saaremaa, and Tartu. Only the Ilūkste branch found it possible to coax not only the clergy (three members of the board), but also the abbess of the Ilūkste Orthodox convent, a local merchant, and a female teacher to take part in its activities [35].

While the branches and their boards did not set lay enthusiasm ablaze, missionary activities in general could prove of interest to a few individuals. The retired lieutenant colonel M. V. Bogdanov applied to become an assistant missionary in November 1912 [36], as did the telegraph operator Kosma Kikkas in December 1914 [37]. On Hiiumaa, the local teacher Kauber found himself in severe debt to a local publisher because he had printed at his own expense 6,300 copies of a missionary brochure he had penned in Estonian [38]. But some priests were equivocal about the benefits brought by such helpers: ‘zealots from the people are the best assistants to the priest in the struggle against sectarianism. But it is undesirable if such people allow themselves complete intolerance and offensive swearing in relation to sectarians. Such swearing absolutely harms the mission, as it causes irritation and bitterness among the sectarians’ [39].

The general activities promoted by RMDC and its branches were disputations with the leaders of sectarian and Old Believer groups, extraliturgical sermons, prayer assemblies, distributing missionary literature, anti-alcoholism lectures, and directing funds to cover travel expenses. The two diocesan missionaries, Pavel and Bucens, were regularly summoned to travel around parishes allegedly under particular threat from other religious groups and to conduct theological debates. However, while such disputations were the most frequently reported method with which the local clergy sought to counter non-Orthodox movements, not all were convinced in the value of such oratorical jousting. Recalling such a competition between Archpriest Vladimir Pliss and an Old Believer officiant, the Latvian priest Father Augusts Pētersons (1873-1955, later the metropolitan of the Latvian Orthodox Church) griped that ‘in these debates, each side attempts (and not always for the sake of revealing the truth) to introduce all kinds of text from Scripture, even if they do not have any connection with the discussed question or fail to clarify it. This is done with the sole aim of not allowing oneself to be apparently defeated by one’s opponent. It also doubtful whether those actually seeking the truth often visit these debates’ [40]. Instead, Pētersons posited that priests should convene missionary circles and explanatory groups in parish schools or private homes to instil better knowledge and religious consciousness among parishioners.

Riga All-Saints’ church

Perhaps the most well-publicised of the RDMC’s initiatives were the so-called ‘popular missionary courses’. From 7 January 1914, these were held twice a week from 20:00 to 22:00 in the parish school of the Riga All-Saints church, with a long break over the summer. Various city priests gave lectures on the Old Believers, sectarianism, Scripture, and church singing: books and other missionary literature were distributed. As Archbishop Ioann (Smirnov) explained, ‘the aim of the courses is to give Orthodox people a correct explanation of Scripture, to protect them from the bad influence of Old Belief and sectarianism, and to train them to protect [others] from non-Orthodox attacks’ [41]. Archbishop Ioann was personally invested in this initiative, regularly attending and giving his own lectures on biblical exegesis. Besides the archbishop and the Riga urban clergy, talks were also given by prominent converts to Orthodoxy, such as Bucens, the former Catholic priest B. D. Kovalevskii, and the one-time Baptist preachers F. Krage and A. Shirmel [42]. The average audience size in 1914, when there were 67 lectures, was 300. The courses even came to international attention, as they were attended by the British theologian and Anglican monastic leader Walter Howard Frere (1863-1938) on 28 January 1914 as he travelled to St Petersburg to deliver lectures and ‘assist with the reproachment and unity of the Orthodox and Anglican Churches’ [43]. But the courses were not as original or groundbreaking as the diocesan administration claimed [44], since similar enterprises were held in Ekaterinoslav, Moscow, and St Petersburg [45].

Among the most important duties of the missionaries and the missionary council was to gather statistical and theological information on non-Orthodox movements, compile narratives about the recent past of said groups, discuss the reasons for their successes (and thus for the failures of Orthodoxy), and propose remedies. Thus, the missionaries engaged in comparative historical and sociological analysis, some of which was published [46]. Many noted the religious dynamism of individual sectarians in spreading their faith: ‘Among the sectarians, every member of the community must be concerned about the spread of their teachings either personally or materially’ [47]. This author argued that the Orthodox should emulate the sectarians in this regard. Others pointed out the poverty of the Orthodox in Baltic provinces. Penning a report in February 1914, Father Ellii Verkhoustinskii, chair of the Ilūkste branch of the RDMC, analysed how Catholic and Lutheran socioeconomic dominance in his district pressured Orthodox households to flee the Church. Verkhoustinskii thus held it was necessary for the Peasant Land Bank to favour landless Orthodox Russian peasants above other groups, especially the Old Believers, when issuing credit for the purchasing of farmland. Furthermore, he suggested, ‘if there are no [Russian Orthodox peasants] in place, then they can even be drawn from the interior provinces: via precisely this path it will be possible to strength the Orthodox element in the parishes’ [48].

Despite the apparent end to police support for the Church in 1905, many of the Baltic Orthodox clergy continued to either recommend or actively seek the forcible suppression of sectarian groups. Father Joann Luks (1871-1940) wrote from the Saaremaa parish of Metsküla on 23 May 1912 that he had asked a constable to close an ‘illegal’ Baptist prayer meeting, although the police refused to do so [49]. In 1913, the Saaremaa branch of the missionary council asked Archbishop Ioann to communicate with the police and circuit court about alleged legal encroachments by sectarians [50]. In October 1912, the archbishop sent several priests (including diocesan missionary Pavel) and sacristans in Riga to attend the sermons of the visiting Baptist preacher William Fetler (1883-1957) so they could watch for any violations of the law [51]: Ioann then asked the local governor to expel Fetler, arguing that the Baptists were harmful to ‘the official principles of our fatherland’ [52]. Ultimately, Fetler was indeed expelled from his home in St Petersburg for his religious activities in 1914 [53].

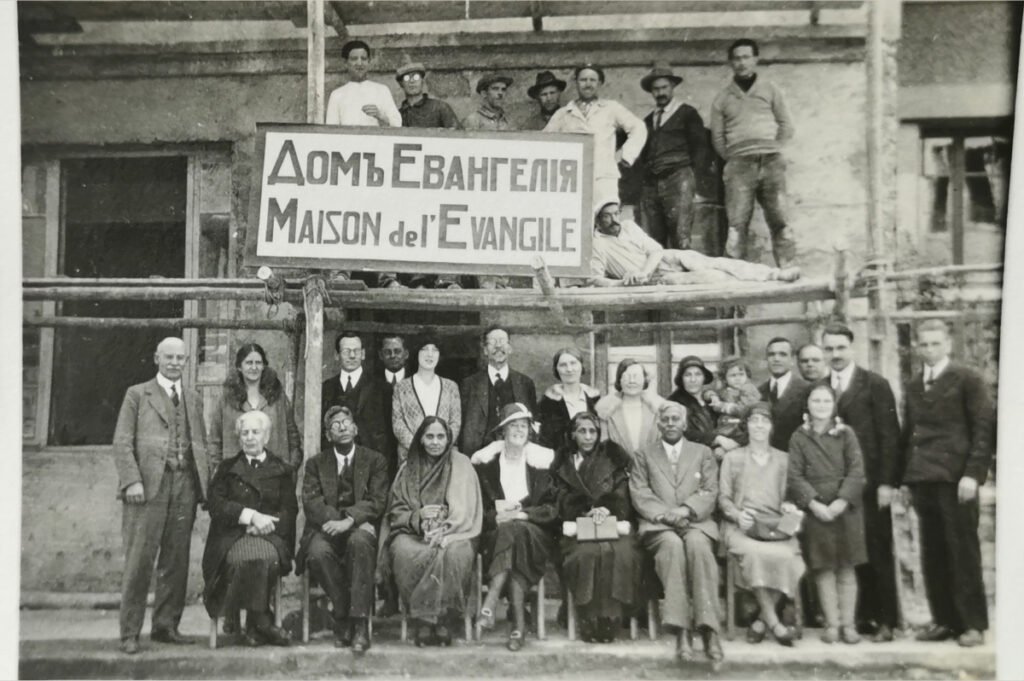

William Fetler and his co-religionists outside their Baptist prayer house in St Petersburg

Following Russia’s entry into the First World War, the German army invaded the Baltic provinces in the summer of 1915, conquering Kurland and part of Livland. Much of the diocese’s personnel and bureaucratic machinery were evacuated from Riga to Tartu, where they functioned until 1919: the same happened to the RDMC. Once safely deposited in the old university town, Archbishop Ioann began holding missionary lectures, an initiative the local branch of the RDMC expanded, creating a schedule for priests to lecture specifically in Estonian both in Tartu and in neighbouring villages [54]. As of 2 July 1916, the missionary Pavel reported that the average number of visitors to each lecture was 300 [55]. There were efforts to expand these lectures to Tallinn, where the most pressing concern was the recent appearance of followers of ‘Brother’ Ioann Churikov, a celebrated (and excommunicated) sobriety advocate [56].

During the war, the Baltic Germans were treated with heightened suspicion due to their alleged links with imperial Germany, the result of which was property expropriations and exile from the area of military operations. For some members of the Orthodox clergy, the seizure of Baltic German land was an opportunity to gain greater economic security. Writing as the chair of the Hiiumaa branch of the RDMC on 30 January 1917, Father Mihkel Vahter (1878-1938) noted how the lack of land and wealth damaged the prestige of Orthodoxy in the eyes of Estonians: he thus demanded that Orthodox parishes should be given estates taken from ‘the traitorous German barons now in Irkutsk province. The only salvation is in land’ [57].

Spymania and militaristic xenophobia in the Baltic provinces also had a religious dimension, since Lutheranism and Baptism were depicted as German faiths. The RDMC directly propagated this stereotype during a meeting on 18 December 1914, proclaiming that since Lutheranism was the religion of the enemy and had failed to prevent German war crimes, mass conversions among Estonians and Latvians to Orthodoxy were now to be expected [58]. Such a result was also foreseen by the Latvian educator and national figure Atis Ķeniņš (1874-1961), writing in a letter to Archbishop Ioann (Smirnov) on 10 August 1914 that Russian Orthodoxy was closer to the soul of the Latvian people ‘than dry German Protestantism, founded on reason alone and lacking mystical poetry’ [59]. The notion of Lutheranism as a German encampment inside the empire was also propagated in a Latvian pamphlet published by the missionary Bucens and Father Jānis Jansons in 9,000 copies [60].

Father Aleksandrs Lismanis

Given the allegedly German character of Evangelical Christianity, the RDMC was particularly concerned about countering sectarian proselytism among active or wounded soldiers. On 15 January 1915, Father Aleksandrs Lismanis (1874-1953) visited an army hospital located on the estate of Princess Lieven near Inčukalns: he was indignant to discover that the princess organised prayer meetings for the hurt soldiers at her manor house while her children played and sung sectarian songs on the piano [61]. Outraged, the Riga diocesan newspaper belligerently bellowed, ‘the insolent heirs of Teutonic heritage – the Baptists, the Shtundists, and Adventism – have dared to ravish not only the chief spiritual treasure of our warrior heroes, not only to take from them their spiritual health, but also to steal them away from hospitals and lead them into captivity with the spiritual charms they inherited from the Germans. Lawless Teutonic marauding thus now takes place not only on the front, but also deep behind the lines’ [62]. The diocesan missionary Pavel, accompanied by Father Lismanis, went to the hospital to inspect the situation, distribute literature, and warn the soldiers that the songs they were singing were not Orthodox [63].

During peacetime, the requests from the RDMC and the Orthodox clergy to the police and courts to suppress sectarian activities had largely not been answered. However, such demands were acceded to during the war, with numerous sectarian groups being banned. At the end of 1914, the diocesan missionary Pavel requested detailed information from the Tallinn branch of the missionary council about sectarians in the city’s shipyards [64]. While initially the Tallinn branch of the RDMC did not believe there were legal reasons to close the meetings, in 1915 the commandant of the Peter the Great naval fortress prohibited Evangelical prayer assemblies and threatened to exile preachers who disregarded the ban: this action was taken apparently out of concern that Evangelical Christianity was spreading from the Tallinn shipyards to sailors in the infamously rowdy Baltic fleet [65]. The police also closed a Baptist community in Kärdla on the island of Hiiumaa in 1915 [66].

Following the revolution of 1917, the diocesan missionary Father Joann Pavel continued his work for a few months, as he thought that the new civil freedoms had energised Lutheranism and sectarianism: this ‘change in religious life should be an object of study for the diocesan missionary’ [67]. To make such observations, Pavel travelled to Velise in the summer of 1917 to hold cross processions, an amateur concert, and sermons, during which he argued that the political freedoms of the new order would be useful for maintaining freedom in Christ [68]. By this point, however, the RDMC had otherwise ceased to function, leaving the torch of Orthodox mission in the Baltic region to be picked up by successor Churches in Estonia and Latvia, where missionaries would indeed have to learn how to convince and convert without access to state funds or police pressure.

Notes

[1] This description of typical missionary endeavours is drawn from H. J. Coleman, ‘Theology on the Ground: Dmitrii Bogoliubov, the Orthodox Anti-Sectarian Mission, and the Russian Soul’ in P. L. Michelson and J. Deutsch Kornblatt, eds., Thinking Orthodox in Modern Russia: Culture, History, Context (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014): 64-84.

[2] Ibid.

[3] J. E. Clay, ‘Orthodox Missionaries and “Orthodox Heretics” in Russia, 1886-1917’ in R. P. Geraci and M. Khodarkovsky, eds., Of Religion and Empire: Missions, Conversion, and Tolerance in Tsarist Russia (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2001): 38-70; D. Scarborough, ‘Missionaries of Official Orthodoxy: Agents of State Religion in Late Imperial Russia’ in R. A. Poole and P. W. Werth, eds., Religious Freedom in Modern Russia (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018): 142-159

[4] V. I. Musaev, Pravoslavie v Pribaltike v 1890–1930-e gg. (St Petersburg: Izdatel’stvo Politekhnicheskogo universiteta, 2018), 158.

[5] Figures for 1911. Ibid., 108.

[6] These figures are to be treated with a grain of salt, since Old Believers and sectarians often hid from census registrars and other officials. H. Schmidt, Glaubenstoleranz und Schisma im Russländischen Imperium: Die Staatliche Politik Gegenuber den Altgläubigen in Livland, 1850–1906 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 2015), 66; Musaev, Pravoslavie v Pribaltike, 126.

[7] C. Gibson and I. Paert, ‘Apostasy in the Baltic: Religious and National Indifference in Imperial Russia, 1860s–80s’, Past and Present, vol. 255, no. 1 (2022): 233–278.

[8] K. Weber, ‘Religion and Law in the Russian Empire: Lutheran Pastors on Trial, 1860– 1917’ (PhD diss.: New York University, 2013).

[9] J. M. White, ‘Changing Tides of Nation and Confession: Building Orthodoxy and Empire on the Island of Vormsi, 1873–1905’, Ab Imperio, no. 2 (2022): 147–177.

[10] Musaev, Pravoslavie v Pribaltike, 78.

[11] Scarborough, ‘Missionaries of Official Orthodoxy’, 147.

[12] J. M. White, ‘Russian Orthodox Monasticism in Riga Diocese, 1881–1917’, Canadian Slavonic Papers, vol. 62, no. 3–4 (2020): 373–398.

[13] ‘O missionerstve voobshche i v Rizhskoi eparkhii – osobenno. (Dukhovenstvu Rizhskoi eparkhii ot arkhiepiskopa Arseniia)’, Rizhskie eparkhial’nye vedomosti (REV), no. 1 (1897): 4-24.

[14] V. Pliss, ‘Rizhskaia eparkhial’naia missionerskaia biblioteka i zadachi pravoslavnoi missii v Pribaltiiskom krae’, REV, no. 21 (1892): 806-811; no. 24 (1892): 965-971.

[15] V. P. ‘Missionerskie besedy v g. Rige’, REV, no. 5 (1889): 179-190; V. Pliss, ‘Sinodal’nyi missioner, protoierei Ksenofont Nikoforovich Kriuchkov i ego sobesedovaniia s imenuemymi staroobriadtsami v g. Rige’, REV, no. 8 (1890): 232-237.

[16] Musaev, Pravoslavie v Pribaltike, 140.

[17] Otzyvy eparkhial’nykh arkhiereev po voprosu o tserkovnoi reforme (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Krutitskogo podvor’ia, 2004), part 1.

[18] ‘Ukaz ego imperatorskogo velichestva, samoderzhtsa Vserossiiskogo, iz sviateishego Sinoda’, REV, no. 16 (1908): 522-524.

[19] ‘XXVII eparkhial’nyi s’’ezd dukhovenstva Rizhskoi eparkhii’, REV, no. 2 (1909): 44-49.

[20] ‘Ukaz ego imperatorskogo velichestva, samoderzhtsa Vserossiiskogo, iz sviateishego pravitel’stvuiushchego Sinoda, preosviashchennomu Ioannu, episkopu Rizhskomu i Mitavskomu’, REV, no. 24 (1910): 758-759.

[21] EAA.1655.2.1346.26.

[22] EAA.1655.2.1349.24.

[23] ‘Prisoedinenie k pravoslavnoi tserkvi nastavniki baptistov’, REV, no. 1 (1914): 23-26.

[24] EAA.1655.2.1351.24ob.

[25] ‘XXVIII eparkhial’nyi s’’ezd dukhovenstva Rizhskoi eparkhii’, REV, no. 1 (1911), 13.

[26] EAA.1655.2.1346.1ob. The board members were Archpriest Aleksander Värat, Father Vasilii Shchukin, Father Jānis Jansons of the Riga church of the Ascension, Father Jānis Jansons of the Riga church of St John, and Father Aleksandr Znamenskii, a edinoverie priest.

[27] ‘Ot Rizhskogo eparkhial’nogo missionerskogo soveta’, REV, no. 11 (1913), 317; EAA.1655.2.1347.56

[28] EAA.1655.2.1351.41.

[29] EAA.1655.2.1347.9-10ob.

[30] EAA.1655.2.1347.18.

[31] EAA.1655.2.1349.64.

[32] EAA.1655.2.1350.1.

[33] EAA.1655.2.1347.59.

[34] EAA.1655.2.1347.20.

[35] EAA.1655.2.1350.34.

[36] EAA.1655.2.1347.51.

[37] EAA.1655.2.1350.26.

[38] EAA.1655.2.1349.104.

[39] EAA.1655.2.1349.62.

[40] A. Peterson, ‘O prikhodskoi missii’, REV, no. 11 (1914): 349.

[41] ‘Otkrytie pravoslavnykh narodno-missionerskikh kursov v g. Rige’, REV, no. 2 (1914), 55.

[42] ‘Narodno-missionerskie kursy v g. Rige’, REV, no. 23 (1914): 681-687.

[43] ‘Narodno-missionerskie kursy v g. Rige’, REV, no. 4 (1914), 101.

[44] ‘Rizhskaia eparkhiia v 1914 godu’, REV, no. 1 (1915), 19.

[45] A. B. Efimov, Ocherki po istorii missionerstva Russkoi pravoslavnoi tserkvi (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo PSTGU, 2007), 411.

[46] I. Pavel, ‘Sektantstvo na ostrovakh Dago i Ezele i bor’ba s nim’, REV, no. 22 (1913): 622-631; no. 23 (1913): 642-658; I. Pavel, ‘Sektantstvo v gorode Revele i mery bor’by s nim’, REV, no. 12 (1916): 366-376.

[47] EAA.1655.2.1349.26ob.

[48] EAA.1655.2.1349.31.

[49] EAA.1655.2.1347.27.

[50] Pavel, ‘Sektantstvo na ostrovakh’, 655.

[51] EAA.1655.2.1347.46.

[52] EAA.1655.2.1349.79.

[53] M. Raber, ‘William A. Fetler in Exile, 1914-1957’, Journal of European Baptist Studies, vol. 21, no. 1 (2021): 141-155.

[54] EAA.1655.2.1351.21.

[55] EAA.1655.2.1351.32.

[56] EAA.1655.2.1351.35.

[57] EAA.1655.2.1351.47ob.

[58] ‘Rizhskii eparkhial’nyi missionerskii sovet’, REV, no. 1 (1915): 28-30.

[59] EAA.1655.2.1349.141.

[60] EAA.1655.2.1349.127.

[61] EAA.1655.2.1350.14.

[62] ‘Religioznoe maroderstvo’, REV, no. 3 (1915), 101.

[63] ‘Kak eto bylo’, REV, no. 11-12 (1915): 335-339.

[64] EAA.1655.2.1350.1.

[65] EAA.1655.2.1351.7.

[66] EAA.1655.2.1351.4.

[67] EAA.1655.2.1351.55.

[68] EAA.1655.2.1351.56.

Author

James M. White

Date Added

5 February 2026

This article was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant PRG1599.